Intelligence Amplification: How EMR Systems Might Actually Help Improve Health Care Delivery

The synergy of humans and computers proffers to improve decision making and enhance the experience of health care—for patients and providers.

Sponsored by Modernizing Medicine and originally appeared in Retina Today.

In my prior experience as a practicing ophthalmologist, I witnessed numerous instances where the intersection of health care and technology produced wonderful advancements in the way physicians care for patients. From enhancements in diagnostic ability to improvements in surgical capabilities, there are myriad examples of how the expertise of humans has been augmented by innovations that yielded greater quantity and quality of care. Even within ophthalmology, one could easily cite the advent of OCT or the evolution of femtosecond laser technology as just two of many such examples.

This holds true for electronic medical record (EMR) systems, as well. In theory, electronic records are a platform that can help to improve outcomes, increase efficiency, enhance patient encounters, positively affect decision making, and otherwise make us better at taking care of patients. More to the point, EMR systems can enhance the important work we do. They can make us more efficient by, for instance, managing clerical tasks so we can be more focused on the needs of patients.

Unfortunately, the promise of EMR systems has been somewhat stymied by their association with an ever-increasing slew of regulations that have very little to do with daily clinical operations. I wonder if the tone of EMR conversations might be different if they could be dissociated from concepts like “value-based care” and “meaningful use requirements.” Might doctors be more willing to accept electronic records if they were perceived as a way to improve efficiency rather than another requirement set forth by the regulatory landscape?

Physicians tend to get uncomfortable in discussions about EMR systems for these regulatory reasons. However, one theme seems to always percolate to the surface: the perception that practicing medicine in a paperless world interferes with patient interactions and that placing a computer between the physician and the patient builds a barrier while removing an important point of contact.

EMR systems don’t have to be dehumanizing. More to the point, we can view these systems as an asset rather than an obstacle to patient care. The incorporation of innovative concepts, such as intelligence amplification (IA), has the potential to simplify clinic operations while providing unprecedented access to powerful data and metrics that facilitate better decision making. There is a better way forward with EMR systems.

Why EMA?

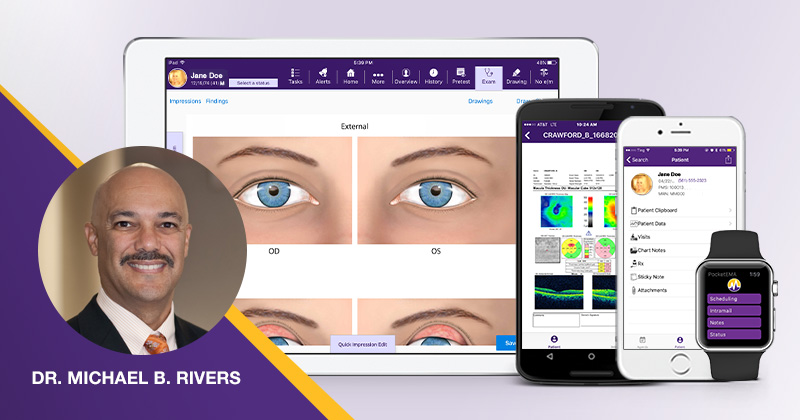

Having worked with EMA, the ophthalmology-specific EMR system from Modernizing Medicine, both as a customer and now as an employee of the company, I can say that user experience is paramount and fundamental to the system’s design. The emphasis on how EMA is integrated into regular clinical operations is apparent from its workflow to its functionality.

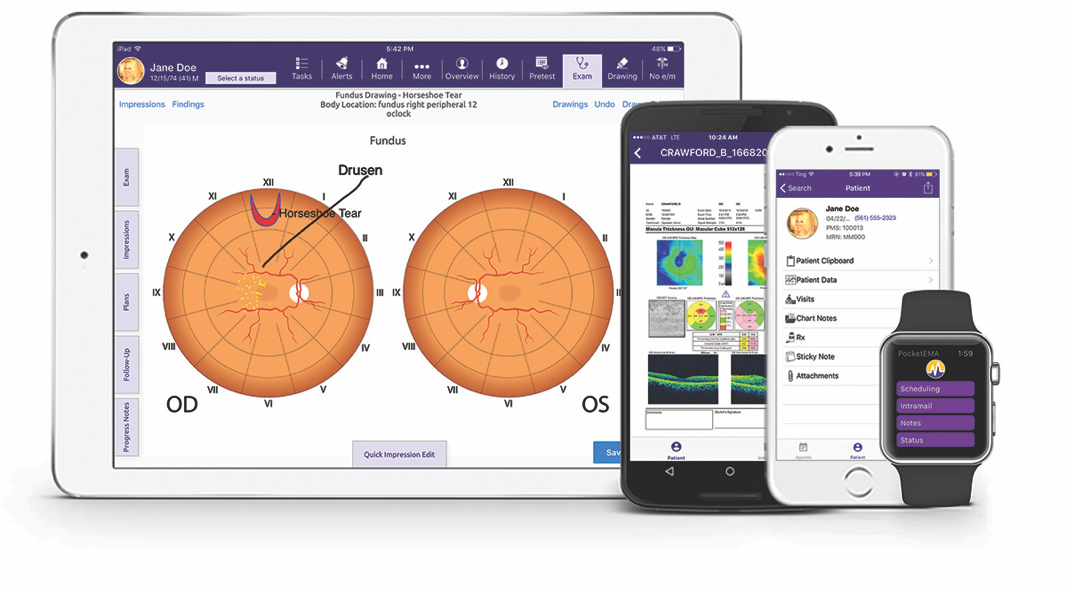

EMA is cloud-based and can be operated from a native iPad application. It solves two core problems many physicians have with EMR systems: time intensive clicking on dropdowns and software not built for our specific needs as ophthalmologists. With EMA, entering information is easy to do with the touch-based system, and the need for specialized scribes is largely obviated. EMA was designed by and for practicing ophthalmologists with feedback incorporated from on-site visits, research panels, and users’ conferences. This information is instrumental to prioritize periodic upgrades and improvements.

EMA also helps providers navigate the evolving regulatory landscape. Now that the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) is a reality, numerous performance measures must be tracked, logged, and reported in order to maintain reimbursements and avoid penalties. Most would agree that these requirements are, at best, a distraction. Some feel they are irrelevant, needlessly time-consuming, and confusing. EMA captures information for MIPS reporting within the flow of the exam as the provider taps the iPad screen. EMA automatically tabulates a MIPS composite score and aggregates data for reporting. Thus, when the ophthalmologist enters the room, he or she can focus on the relevant parts of the examination without being distracted by asking questions that have no bearing on the chief complaint.

Information Technology at the Point of Care

Electronic records can be designed to augment and enhance capabilities in the clinic. Where EMA has real potential, though, is in helping individualize care and enhancing the capabilities of the physician through the use of IA.

IA describes the use of computers to improve human decision making. IA is conceptually different than artificial intelligence (AI), which can be loosely defined as the simulation of intelligent behavior in computers. Whereas AI might substitute for human decision making, IA is intended to save the physician time by taking care of tedious tasks and deliver powerful and actionable data to the physician at the time of the patient encounter so that he or she can make a more informed decision.

EMA’s adaptive learning engine recognizes the practice patterns of its user, in turn populating the workflow with the most commonly used elements. At a very basic level, this means that the retina specialist will not be prompted to fill forms with data relevant to the cornea specialist. As the software learns how the user practices, items such as lists of suggested diagnoses or most commonly prescribed drugs are presented on the iPad screen while in the examination room. Less frequently used diagnoses are easily accessible; having the most relevant items for data entry show up makes the exam more efficient.

No two eye care providers practice the same way. Anterior segment surgeons require different functionalities than a glaucoma or retina specialist. Modernizing Medicine’s on-staff ophthalmologists have built EMA’s workflow tailored to the specific needs of each subspecialty. In addition, Protocols lets you create master visits for common conditions, procedures, or postoperative visits, then apply this information to any future exam. In a few clicks, you can record comprehensive patient, procedure, diagnosis, and treatment data, and generate a note and bill just as you would for a regular visit.

This aspect of IA, though, only considers the perspective of the individual. IA could yield an even more powerful effect on physician decision making if physicians could also consider suggested clinical guidelines at the point of care and data points gleaned from analyzing similar cases. Drawing on clinical evidence at the time of the patient encounter could enhance diagnostic and treatment power to improve outcomes and quality of care.

Health care is constantly evolving and changing. In the midst of daily practice, it is easy to lose track of the latest data or the newest understanding in evidence-based care. And as health care transitions into the era of personalized care, physicians feel increasing pressure to retain voluminous data, to analyze and parse it out based on the context of the patient encounter, and to enact a treatment plan for the individual patient.

EMR systems, then, become a way to help manage the windfall of information at the disposal of the physician. IA provides a way to sort through the data, analyze it in real time, and present choices to help the patient make truly informed decisions. Plus, IA can reduce burnout and help physicians save time by taking care of endless tasks and doing work we don’t want to do, such as paperwork, insurance, prior authorizations, requests, regulatory reporting, and more.

Conclusion

Much of the resistance to EMR systems seems to center on the idea that patients don’t go to their doctor to see a computer; they go to see a human professional who will listen and help solve their problem.

However, we should welcome a world in which information technology can assist the care provider while he or she interacts with a patient. EMRs can be part of the solution by helping with subjects like data analytics. On a more basic level, if an EMR system helps manage clerical tasks and regulatory requirements, it gives the doctor time to actually look the patient in the eyes and hear what he or she says.

Information truly is powerful. The advent of technology in health care has generated far more positives than negatives, and there is lost opportunity in ignoring the power of innovation to enhance human capabilities. In much the same way that ophthalmologists have embraced new diagnostic modalities and surgical platforms, it may be time to rethink our expectations of EMR systems. We risk losing advantages of a powerful tool to help make us better doctors if we look upon them as foe rather than friend.